Butler Breeding Built a Bloodline

By Darol Dickinson with Lorna D. Bremner

Texas Longhorn Journal, May/June, 1984

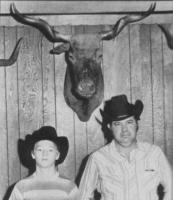

This photograph of Milby Butler also shows one of his prize Longhorn skulls. |

The success of the bull Classic and all of the Butler Longhorn family is founded on the dreams of a man who could be labeled either a visionary or an eccentric. Milby Butler devoted the last decades of his life to breeding a unique strain of Texas Longhorns. He achieved his goal, and the effect on the breed will never be erased. His methods were unclear and his philosophies almost peculiar, but the results can't be denied.

League City, below Houston in the southeast corner of Texas, was Milby Butler's stomping grounds since birth in 1889. At first, the post office of the community bore the name Butler Ranch - G.H.& H. The community that followed then adopted the name Clear Creek. The town that followed changed the name to League City. Milby once stated, "I've lived in three different towns in my life, but I've never moved."

Milby Butler's father, George W. Butler, had owned stock pens where the Butler Ranch joined the G.H.& H. Railroad. Tens of thousands of Longhorns came through the pens. During one period of time, 49,000 Longhorns were shipped to Cuba. The cattle were always unloaded in the Butler stock pens on their way from Houston to Galveston. George Butler also owned a Longhorn slaughtering house. The skins and tallow were sold and buttons were made from the horns. Meat was not that important due to storage limitations prior to the refrigeration methods of today.

In the early twenties, cow trader Perry McFadden brought 10 to 15 thousand head of native east Texas cattle annually to the open range areas at League City. This tall grass, partially timbered lowland area was ideal for a fast economical gain. Several other early day cowmen took advantage of the same area and established the beginnings of vast cattle empires.

With the open range, and with moving cattle in and out, area roundups became the highlight of the year, especially for Milby's son Henry. From the time he was ten, Henry helped with the riding, roping and branding, and took his pay in heifers. I always picked out the big-horned ones," Henry said. The origin of these cattle was "just old, big-horned east Texas cattle. They were all over the country in those days," according to Henry.

In this 1979 photograph, DeWitt Meshell and son Randy pose under mounted head of Miss John Wayne. |

He kept these cattle, and they became an important part of the Butlers' foundation herd. DeWitt Meshell, Trinity, Tex., who was a friend of Milby's and helped out on his ranch for several years during the 1960s, believes that the Butlers' seed stock was also composed of descendants of George Butler's herd and Longhorns gleaned over the years from the Butlers' stockyard operation.

Prior to the 1930s, it was not any trouble to acquire big-horned cattle in many parts of south Texas. There were thousands of different families of Longhorns from which to get new and different cows or bulls to maintain or improve a herd. As more Brahman and English blood was crossed on native cattle, the pure Longhorns became more scarce. In order to preserve Longhorn herds, a special effort had to be exerted to locate top blood.

In 1931, the Butlers traded Pat Phelps of Newton County two Brahman cows for a white "flea-bitten" Longhorn cow. This white, speckled cow with red ears, red rings around the eyes and nose, and red specks on the ankles became the first source of the color trait many people refer to as "Butler color".

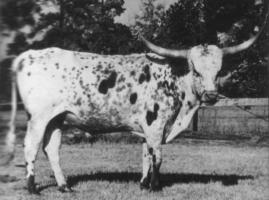

|

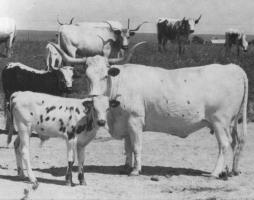

Above: Beauty, with 51-inch horn spread, was the dam of Classic, Reveille, Butler Boy and Centennial.

Below: Ghost, typical of the bigger Butler cattle, weighed 1,200 at age 11. |

|

M. P. Wright III of Robstown, Tex., said, "We bought some Butler cows in the first TLBAA sales. That white color with the red or black ears became the most dominant color in our herd." Henry described the "flea-bitten" cow as a medium-sized cow with a double twist corkscrew horn shape.

In the earlier years, Milby's attention was taken up more with his Brahman cattle than with the Longhorns. He was involved in establishing some of the first registered Brahman cattle in the area. Herds all over the South still claim to have Butler Brahman blood as the nucleus of their best breeding stock. But when Henry was away in the service during World War II, Milby had an opportunity to work more with the Longhorns and became more interested in the breed. He assumed active responsibility for the ranch's Longhorn breeding program.

Milby, in his search for outside Longhorn blood, purchased five cows from Esteben Garcia of Encino, Tex. These cattle were not the east Texas variety. They were true Mexican cattle. They came off a dry desert and had been living on cactus most of their lives. They had calluses on their knees and hocks from getting up and down on rock and cactus. Their mouths were so full of pear spears that their muzzles looked like a porcupine's back.

When the cattle were transported to League City, three died and two lived. These cows, although an entirely different bloodline, bore the Butler trait of huge horns with corkscrew twists.

One cow was red with a white star on the forehead. Christened Miss John Wayne, she lived to be 37, giving birth to 12 bulls and no heifers. These sons were used for out-cross Longhorn blood on the original Butler herd. At one time, a fellow Longhorn enthusiast offered Butlers $2,000 for this cow, but didn't get to own her. That was when a cow would only bring $130 over the scales. Milby had her head mounted when she died, and it is now in the possession of DeWitt Meshell.

The addition of the Mexican cattle was Milby's last big attempt to introduce new blood to the herd. He tried a few more times to add outside blood, but was never very successful. In the early 1960s, Milby borrowed a two-year-old wine-and-white speckled bull from Gerald Partlow of Liberty, Tex. Partlow had leased two or three bulls from Graves Peeler and didn't need the one extra. Milby was glad to get a bull of unrelated blood. (This is the only bull we ever found Butler using that he didn't raise.) Butlers did not feel the Peeler bull had the horns they wanted but he was unrelated and a very pretty color. Henry says they only used him on a few cows because one of the bigger bulls killed him.

In 1965, Milby Butler attended the Wichita Refuge Longhorn Sale and purchased two cows. One was WR 2197, a black-and-white daughter of WR 1790. Both cows were hauled by a friend from Cache to a ranch west of San Antonio. One cow died on the way home and Milby never went after the other one.

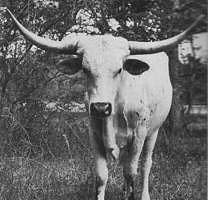

Classic |

Thomas |

F. M. "Blackie" Graves, Dayton, Tex., one of the first to acquire any of Butler's cattle and half-owner of Classic, describes another of Milby's tries at adding to his herd. "Mr. Butler didn't have any black cattle in his herd. One time we were at a sale when the association was first started, maybe in San Antonio. Milby told me, 'I don't have any black ones,' and he bought a black cow. It never did make it to the ranch. Somebody stopped it off at their place, and he never did go pick it up.

Milby's half-hearted efforts were due partly to the fact that adding any untested outside blood to his herd worried him more than the threat of inbreeding. But more than that, according to DeWitt, Milby was injured in a ranch accident in the early 1960s. Some hay fell on him and broke his hip, and as he was over 70 years old, he never fully regained his vigor. He was unable to do as much with his cattle as he would have liked in the last years of his life, although his enthusiasm for the breed remained undiminished.

Says Blackie, "I know he was incapacitated a lot of that time, 'cause I was going down there pretty often to see Henry and visited Milby, too. His house sat kind of in his operation, where he could see the barns and pens, and some pasture came right up to the house. And he'd sit there and watch out the window and see what was going on."

Henry worked on his dad's ranch off and on over the years and, along with Milby's secretary, Pauline Russell, made sure the ranch ran smoothly during the periods when Milby couldn't be up and about. Blackie recalls, "Henry was a first-class cowhand. He had done that all his life." DeWitt agrees, 'Henry was an all-around hand, what you'd call a good cowboy."

During the mid-1960s, Garnet Brooks worked as a registration inspector for the newly-formed TLBAA. He saw the Butler cattle on two different occasions. Brooks' comment to TLBAA in his regular notes indicated the following, "The Butler cattle were mostly light colors of cream, dun, grulla and white speckled. I did not see any black cattle. The pastures were partly chain- link with excellent gates and working pens. There were many old cattle with the Texas twist-screw type horns. They were unusual cattle and different from other Longhorn herds. They were a bigger-framed cattle than most south east Texas cattle. Many of the cattle could be considered real outstanding on horns."

At the time of the second inspection, some months later, Brooks went to Butler's home and picked him up. The elderly gentleman was crippled and couldn't drive himself, but was still very excited about showing Brooks the cattle. Brooks recalls, "Mr. Butler had been a big man. He was pleasant and kind to me even though I was sure he suffered much pain while I was there. Again we saw an identical type of twisted big-horn cattle. The cattle were very uniform. They were selected for a specific type of his own desire. He felt he had a true type of the old blood."

Reveille |

Butlers used many white and roan bulls as herd sires. Their main cow herd had been dominated by the solid colors, as found in most herds of that day. By breeding white bulls on solid cows, many unusual and outstanding colors were the result.

"He really did have the doggone color in his herd," says DeWitt. "He had grulla, dun, blue-faced and had a bull just about every color. Beauty's mom, Fawny, was a dun. Her sire, Smarty, was a pale red. Bevo's mom was a real dark brown with a brown face."

Blackie remembers being similarly impressed with the color in the Butler herd. "He had some linebacks and a good many brown cows, and a lot of these white cows that had the big red spots on them. Not speckles, but big red spots six or eight inches around. This is the coloring that Sam and Man 0' War had. Milby had a few red roan cows and I'm sure he had a few brindles, but they weren't real prevalent."

Sam |

Sam Partlow, an early TLBAA director whose family has long been involved in the Butler line, comments, "Milby wanted the mealy-mouth on his Longhorns." Jack Phillips, breeder of Texas Ranger J.P., and an early associate of Milby's recalls, "He had a lot of solid red, some brown, but mostly solids. He got more brindle, spotted and lineback calves with a bull he used later on."

DeWitt described Milby's ideas on selective mating. He had about seven pastures of Longhorns. Each cow was selected for that specific bull. Fences were built dividing his pastures that were virtually impossible for cattle to get out of. Certain bulls were mated to line breed certain bloodlines. He had methods of obtaining percentages of certain bloodlines then crossing them back on other lines within his herd."

On the Milby Butler herd sires, J. W. Isaacs comments, 'I don't know what his selection rules were for herd sires but, somehow, he had an eye for picking superior breeding bulls second to none. He didn't use anything but very out standing bulls."

Says DeWitt, "Nobody could ever pick a sire like he did." The herd sires consistently had dams in the "outstanding" horn category. Milby felt a top bull had to have a superior mother. Most of his sires were out of the corkscrew-type horned cows.

"I don't know what he knew about genetics, but he apparently knew something because he got the horn growth," says Blackie. "I know he was interested in horn growth. He was the only one that ever talked horn to me. I think he was emphasizing and breeding for horn when maybe none of the rest of them were trying to get that much horn. My bull Sam that I got from the Butlers had a lot of horn, but it came around forward. But the old cows I raised with wide, twisty horns came out of that bull."

DeWitt comments, Milby was a horn man, really. He never did talk about any thing else with his Longhorns. He bred back for horn base. Milby always said, 'If you get the base, then you can always get length, but without the base the horns will always get smaller." Sam Partlow concurs. Milby liked a big base on the horn, with a high crown. He was striving for big horns."

Holman B1 |

Bold Ruler |

The bull Butler Boy, by Milby's Bevo and Beauty, has a horn base that measures 15 inches in circumference, according to former owner Wiley Knight, who bought the bull from Pauline Russell. He also has a three-year-old heifer out of Party Girl, a Partlow Butler cow, whose horns are 11 1/2 inches around at the hairline. So it would seem that Butler's preferences have passed down through the cattle to some extent.

Milby was extremely interested in the horn aspect of his cattle and developed some rather unusual ideas in that area. Walt Osterman of League City reflects, "When I was a kid, we used to help Milby with his cattle. He would have us kids gather the big-horned ones every so often and thoroughly rub lanolin into their horns. He wanted their horns healthy and shiny looking. If one nicked or splintered a horn, we were to rasp and sand it back down smooth so each appeared flawless."

Blackie confirms that this story is true and adds, "He told me one time that if you raised your Longhorns in a wooded pasture they'd grow more horn, because the sun wouldn't dry them out as much, and they'd rub their horns against the trees and that would help the horn growth. I've seen a bunch of old steers in a park here rubbing their horns on the trees, and they're killing all the trees. Now Milby's pastures didn't have any woods, but he also said that when the cattle eat the vines and bushes and brush they get different things out of them. And we all know Longhorns will eat the heck out of those things, where other cattle won't. He felt that would stimulate the horn growth, too. That was one of his ideas, and he's the only person that ever told me that."

Lone Ranger |

In a 1966 catalog for a TLBAA trail drive, Milby, when asked how Longhorns have gradually changed, said, "The most noticeable change is in the thickness of the horns. The horns get perpetually thinner."

Milby's interest in horns led to his skull collection which he was equally avid about. Whenever a cow died, Milby kept the skull. He would clean it up so it was dry, bleached and white. He wouldn't let go of a skull, either. The life history of every skull was quickly related to anyone genuinely interested.

Milby had somewhat different ideas when it came to selling his Longhorns, as well. For years he said he wouldn't sell any, no matter what. If another Longhorn breeder wanted to buy a bull, none was available. Yet, to the contrary, he might just give away a pasture full if he liked you. DeWitt Meshell recalls several instances where he loaned out up to ten cows and a bull for several years. After a nucleus of calves was raised, the cattle would be returned and the borrower was well-started in the Longhorn business. According to DeWitt, Milby loaned bulls to Barney Griggs, Dode Partlow (Sam's uncle), Blackie Graves and J. W. lsaacs.

Says Blackie, "Milby steered most of his cull bulls and he wouldn't hardly even let anybody have a steer. He did have a lot of steers." DeWitt notes that Milby would loan out steers by the bunches, though.

Back in 1951, Milby unintentionally sold a bull to Jack Phillips. Milby had a mottled brown bull that he had picked out as a herd sire prospect, but it kept wedging under the chain-link fence of his bull pen and getting out. Milby just wasn't going to tolerate this nuisance, so he sent him to the Blue Ribbon Packing Company at the Port City Stockyards to be slaughtered. A friend of Jack's saw the conspicuously long-horned bull and, knowing that Jack was accumulating Longhorn cattle, gave him a call. He told Jack that a big, flat-horned bull was being sold by Milby Butler. Jack made a deal to buy him, and for years both he and Graves Peeler used the bull on their cows. Says Jack, 'Milby was mad at me for buying the bull, but he must have gotten over it, 'cause later he came down and bought a bull from me." Jack reports that he had no problems with the bull, and says it threw lots of horn and color.

Due to poor health, Milby didn't participate in the 1966 trail drive from Texas to Dodge City, but his steers were there. |

The few times Milby did sell any of his cattle, it was usually more for personal reasons than business. In 1966, he sold four heifers and a bull to Virgil Shinn of Idaho, and he threw in a steer, too. Milby and Virgil had a mutual friend, a rodeo cowboy, who arranged the deal. He sold some to the Partlows because, as Blackie says, "He and Dode Partlow were both old cowmen and they got along real well."

Blackie first saw the Butler cattle in 1961 and wanted to buy some right away, but says, "I guess it was a year before Mr. Butler sold me any. I think he was eccentric. I don't think he wanted anybody to have his breeding and what he'd done with his Longhorns. You know, the average cowman didn't value them back then."

Milby was very enthusiastic about the formation of the TLBAA. He registered about 20 bulls and 300 cows during the first years of the organization. He wanted to participate in the 1966 trail drive from Texas to Dodge City, but failing health wouldn't allow it.

Edwin Dow, an early TLBAA director, remembers contacts with the elderly Butler. 'He used to come to TLBAA meetings and sales. He was really quiet. We really had no idea he was raising a select group of Longhorns like the Butler cattle proved to be."

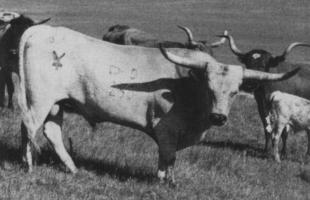

Jumbo Horns, owned by Red McCombs |

He's A Ten, owned by Maribeth Vineyard |

When the TLBAA-sponsored sales started at Houston, San Antonio and Fort Worth, Milby consigned several cows to help out. It was hard for him to let go of his top cows. Henry said, "He only consigned cows that were not as good as the ones he kept. It really hurt to even think of letting go of the outstanding ones."

Once a vet came out to work with one of the cows and noticed several cows were completely smooth-mouthed. He advised Milby to sell them for hamburger before they died of old age. Milby wouldn't even discuss it. He always thought as long as they were alive, there was another chance for one more good calf.

He was probably right. Milby managed to raise a number of outstanding calves from those good cows of his, with the help of a superior battery of herd sires. He and Henry raised an impressive list of herd sires on their ranch, including Smarty, Bevo, Sam, Man 0' War, Thomas, Lone Ranger, Conquistador, Ken, Pappy L, Riverio, Homan B-1 and Tommy. Out of these have come what Blackie terms a "new generation" of Butler bulls with names such as Classic, Jumbo Horns, El Patron, Monarch, Reveille, Butler Boy, Bold Ruler, Pete, Stetson, 3S Spectacular, Blue Horns, Colorado Cowboy, He's A Ten, YO Centennial, Milby 1/2, Boomtown and Holman B-3. These in turn are distributing the Butler attributes through herd after herd, with the help of artificial insemination and embryo transfer.

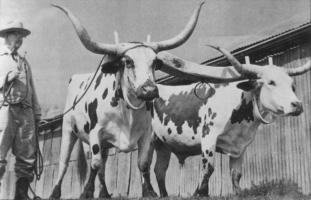

R.G. Partlow, shown here with his Longhorn oxen, had some cows from Milby's herd. |

At the time of Milby's death in the early 1970s, his cattle were very inbred. He searched for outside blood for 20 years that would not lose his huge-horned bloodlines, yet give different genetics. But he didn't have the heart to allow a bull with his beloved corkscrew-horned females just for the sake of different blood. So, the herd continued on an intensive inbreeding course. Blackie Graves and others feel that this has been a contributing factor in the extreme horn growth. But many feel that the tremendous horn growth could also be the natural culmination of Milby's many years of breeding for the characteristic.

We're fortunate to have Milby's cattle and their descendants that are alive today. There are several versions of where and how his cattle were dispersed, but we do have some concrete explanations. Some of the Butler cattle were part of Milby's wife's estate, and were sold by private treaty when Mrs. Butler died a year or two prior to Milby's passing. J. W.lsaacs was among the private treaty buyers, purchasing 14 two-year-olds.

Immediately following Milby's death, the bulk of his remaining cattle were auctioned off. Some went to slaughter, and others were bought by Longhorn breeders fortunate enough to find out about the sales, including DeWitt and his brother Sammy Meshell, Ruel Sanders, Sam Partlow, Mr. Holman, and J. W. Isaacs. The average price brought for the Butler cattle at one sale was $170.

Pauline Russell kept at least 20 of the best Butler cattle, which she sold in 1977 at the Raywood Auction (east of Liberty, Tex.). Classic, Reveille, Monarch, Butler Boy and Lady Butler were all sold then. Says Blackie, "I bought two bulls there for Doc (Ed) Stephenson, and some of the other buyers were W. D. Partlow, Wiley Knight and Edward Faircloth. The bulls were just little yearlings and were all in very poor shape. I bought Classic, but I wasn't really all that impressed with him. He was poor and he was solid white - he just had a lot of horn."

The complete history of the Butler cattle may never be known. Occasionally, a bit of fact will be uncovered as evidenced by an old skull or a scrapbook weathered with age. Yet, from the history we have gleaned, one can appreciate a family whose untiring efforts included the annual excitement of planning the genetics of a calf crop better than the last. Without a doubt, Milby Butler would be very pleased if he could see today the impact that his prized cattle have had on the entire Texas Longhorn breed.

Material is courtesy of LonghornJournal.com

|